A Casual Look at the Bias-Variance Dilemma

Making predictions is one of the main ambitions of the human race. One may have the motivation to forecast almost anything from a sports event to the stock price or his girlfriend’s mood… But the future is a random variable – no one really knows how it’s gonna be, so any prediction is in essence a “guess”. Well, how to guess then? You can simply toss a coin, this is quite convenient, but it certainly does not give the best guess possible. This is where statistics comes to stage, as I define briefly that knowledge field as “the science of guessing”.

While the future is an inherent mystery, the past is an environment where uncertainty doesn’t exist anymore, so it’s only natural and reasonable trying to predict the future based on what has already happened. Roughly, based on elements (a list of \(x_1,x_2,...,x_k\) independent variables) that may have influence on the variable to be predicted (a dependent variable \(y\)), the goal is to try and guess future values of \(y\) by collecting new values of the \(x\)’s (in machine learning, the jargon for this is “supervised learning”). That is, statistics seek to provide the best guess, conditioned to the available information.

Think intuitively: even though the future may bring in stuff completely different from anything seen in the past, it’s reasonable to assume that both future and past share certain patterns, connections that make those two temporal instances a manifestation of the same phenomenon. To get good guesses, a very important concept is called bias-variance dilemma.

What does it mean exactly?

Let’s first discuss “bias”. It’s easy to imagine that in order to accurately predict the future, one must first understand the past well. A predictor that fails to map clearly the characteristics of clearly observed data tends not perform badly for the future. What we call “bias” are the deviations between the observed in the past and the predicted by the proposed model – in short, how well the model is describing the observed data.

It is natural to think that the better the model describes the sample data, the better it is. But this is not true, since the primary purpose is not to describe the data, but rather to use those to make predictions (or inferences) about the future. This brings us to the “variance” side:

Our goal here is to be able to predict the variable of interest \(y\) based on some elements of the whole population, so we have a major problem from the start, for what we actually see in the sample is only part of the whole phenomenon; so if we simply stick onto describing the already available data, we essencially hoping that the same pattern will repeat in the future, which clearly doesn’t always happens. To be able to generalize what has been observed for future samples – that is, to anticipate something that has not yet happened – one must calibrate the model for it to capture only the “essential” information that actually contributes to a good prediction, instead of fully capturing the patterns of that particular sample, because in doing so, useless information (“noise”) is incorporated at the same time. Basically, by forcing a very accurate description of the sample data, we end up losing in generalization ability, since, in general, the future is not a mere extension of the past.

Models that describe the data of a sample excessively well tend to introduce a lot of complexity and volatility, thus hindering the generalization ability. In the philosophy of science there is a principle called Occam’s razor (the statisticians know it as the “principle of parsimony”, popular culture has adopted a rather pushy mnemonic:

“KISS – keep it simple, stupid“

Basically, it means that between models with the same explanatory power, the simplest of them is the best, because it presents the same quality with a lower cost.

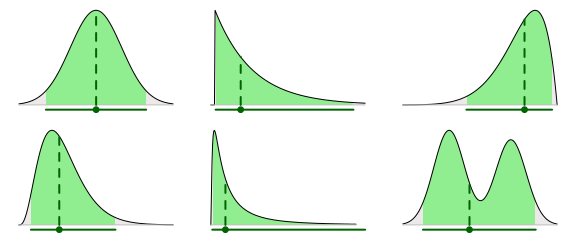

By now, you should have realized that we indeed face a dilemma, as the ideal scenario demands two desirable but contradictory features: we want a model that describes well the available data AND is capable of generalizing for future data. If we fit a model that misrepresents past data (“under-fitting”), the model is kinda unreliable from the start. On the other hand, an over-adjustment (“over-fitting”) ends up assuming that the future will repeat the past, so the model tends to provide a poor prediction even for observations that follow just slightly different trends than the one showed in past data.

The bias-variance dilemma is very important in the mathematical modelling: the quality of a model depends directly on the variables considered, and the optimal middle ground between incorporating useful variables and discarding useless variables can be quite a challenge. Let’s look at a simple example: Suppose that we want to construct a model to predict a company’s stock price. Is to be expected that the economic performance of that company influences decisively on the stock price, so we can put as variables some indicators like index of profitability and liquidity, the company’s market share, number of subsidiaries, and so on.

For instance, we could put “CEO’s scholarity” as an explanatory variable; It is to be expected that a manager with a more robust academic background can increase the value of the company, but the relationship doesn’t seem that straightforward… We could insert as a variable whether the CEO is right-handed, left-handed or ambidextrous, but this information tends not to influence the predicted variable at all, and the introduction of this variable would end up polluting the model with an unnecessary complexity.

Note that there’re no limits to the researcher’s creativity, and theoretically we could put a gigantic number of variables. But as less relevant variables are inserted, there comes a time when the “variance” introduced by the new variable does not compensate for the explanatory power that it adds to the model.

Knowing how to find the ideal middle ground between bias and variance is not an easy task, there are several techniques to aid us with this, such as cross-validation and dimensionality reduction, we can address these topics in future posts.