Machine learning

Formally:

Machine learning can be defined as a computacional system Machine learning and defined by a computational system that seeks to perform a task \(T\), learning from an experience \(E\) seeking to optimize a performance \(P\)

Well, but what does that exactly mean?

Basically, an algorithm can learn a goal, based on a large volume of data - its experiences. Here’s an example to make it clearer: Suppose our task is to predict the outcome of a football game. How can we do that?

We could provide the computer with data about the manager, the squad composition, tactical line-ups, etc., followed by the match results. With a large volume of data in pairs like (variables, results), we expect the computer to learn tha patterns that lead to victory. We also expect the computer get more accurate predictions as we feed it more datato, as it will have more examples of patterns that can generalize for situations not yet seen. Thus, the more data that is, the more experience the computer gets, and the better are the results, that is, the better our performance

Supervised learning

This is what we call Supervised Machine Learning: When we try to predict a dependent variable from a list of independent variables. For example:

| Independent variables | Dependent variables |

|---|---|

| Years of experience, Training background, Age | Salary |

| Age of Car, Driver Age | Risk of Automotive Accident |

| Text of a book | Literary Style |

| Temperature | Ice Cream Sales Revenue |

| Image of a Highway | Steering angle of a self-driving car |

| School Records | SAT Score |

It should be noted that a basic structure of supervised learning systems is that the data we use to train them contains a desired response, that is, it contains a dependent variable resulting from the observed independent variables. In this case, we say that data are labelled as answers or lessons to be predicted.

Among the best-known techniques for solving supervised learning problems are linear regression, logistic regression, artificial neural networks, kernel machines and devices, decision trees, k-neighbors, and naive Bayes. Supervised machine learning is an area that concentrates most successful applications and where a majority of problems are already well defined.

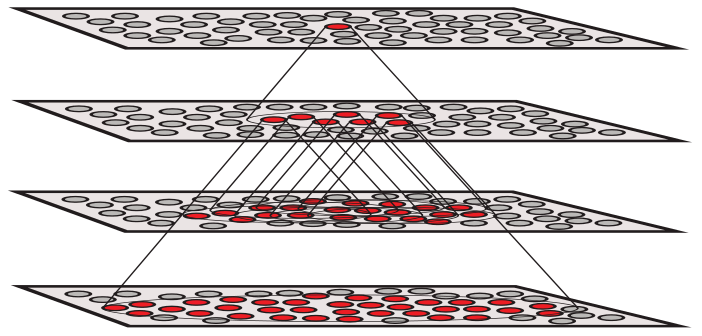

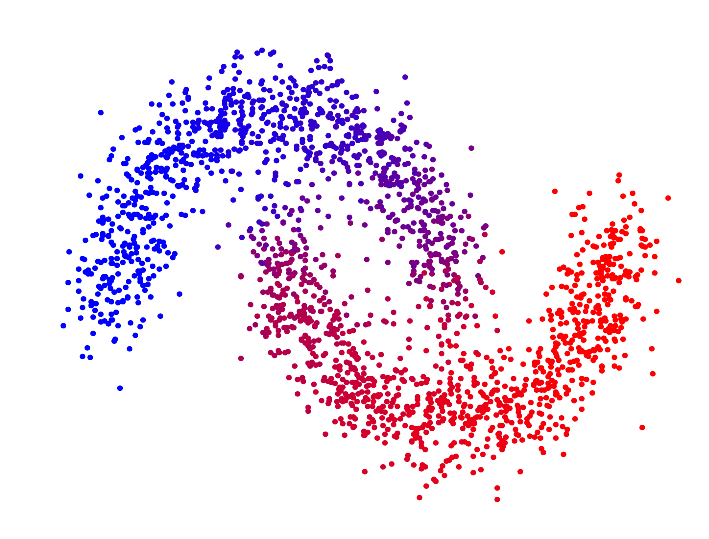

Unsupervised Learning

But not all problems can be solved in this way. In some cases, getting labelled data is extremely costly or even impossible. For example, imagine that you own a business and want to know the profile of your consumers. There may be a consumer profile that always buys wine and cheese, or meat and charcoal, or milk powder and diaper. If this is the case, putting these products on distant shelves can increase sales, since it will increase the time and the customer’s path in the market. However, in this case we are not “labelled” for each purchase to which profile the consumer belongs. Furthermore, we don’t even know how many consumer profiles there are.

In this case, the computer will have to find out the profiles without any labelled data and we will need unsupervised learning methods. One option would be to look whether there are repeated patterns in the purchase records that would allow the inference of a consumer group or profile. Another option would be to directly see which products are often bought together and then learn an associative rule between them.

In general, with unsupervised learning we want to find a more informative representation of the data we have. Generally, this more informative representation is also simpler, condensing the information into more relevant points. Some examples are:

| Data | Representative form |

|---|---|

| Banking transactions | Normality of the transaction |

| Purchase Records | Association between products |

| Multidimensional Data | Data with reduced size |

| Purchase Records | Consumer profile |

| Words in a text | Mathematical representation of words |

Other examples of unsupervised learning applications are movie or music recommendation systems, anomaly detection, and data visualization. Among the best known techniques to solve unsupervised learning problems are artificial neural networks, Expectation-Maximization, k-medium clusters, support vector machines (kernel machines), Hierarchical Clustering, word2vec, principal components analysis, insulation forests , Self-organized maps, restricted Boltzmann machines, eclat, apriori, t-SNE. Unsupervised learning problems are considerably more complicated than supervised learning problems, mainly because we do not have the labelled answer in the data. As a consequence, it is extremely complicated and controversial to evaluate an unsupervised learning model and this type of model is at the frontier of knowledge in machine learning.

Reinforcement learning

The third approach to machine learning is called “reinforcement learning”, in which the machine tries to learn the best action to take, depending on the circumstances in which this action will be performed.

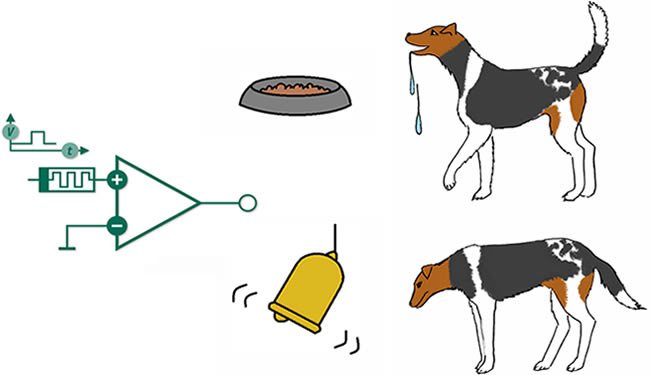

The future is a random variable: since we do not know a priori what will happen, an approach that takes this uncertainty into account is desirable and can incorporate any changes in the environment of the decision making process. This idea indeed derives from the concept of “learning by reinforcement” from psychology, in which a reward or punishment is given to an agent, depending on the decision made; through the repetition of the experiments, the agent is expected to be able to associate the actions that generate the greatest reward for each situation that the environment presents, and to avoid actions that generate less punishment or reward. In psychology, this approach is called “behaviorism” and has B. F. Skinner as a leading exponent, a famous psychologist who, among other experiments, used the idea of rewards and punishments to train pigeons to conduct missiles in World War II.

This same idea is seen in machine learning: the machine observes a “state of nature” from the set of possible future scenarios and, based on this, chooses an action to take and receives the reward associated with that specific action and in that state, thus obtaining the information of this specific combination. The process is repeated until the machine is able to choose the best action to take for each of the possible scenarios to be observed in the future.

Illustrating with a very simple example: suppose you want to train your dog to sit at your command using this approach. At first, your pet will hardly perform the required command, and you respond by giving a “negative reinforcement” (punishment), scolding it verbally, with your facial expressions or even hitting it with a newspaper (or something more hostile, depending upon your temperament …). When the dog gets close to what it should do, you can give “positive reinforcements” as signs of approval or encouragement. If the dog does sit down after the command, you give him a reward - a cookie, for instance. With several repetitions of this same experiment, it is expected that, over time, the dog will associate the cause-effect relationship between the command and the reward to be received, and thereby “learn” to obey this command. The famous “Pavlov’s Dog” experiment illustrates this learning paradigm well. Ivan Pavlov was a Russian scientist notorious for presenting the idea of “conditioned reflex”, based on the following experiment: presenting a piece of meat to a dog, the animal starts to salivate, wishing for food. Instead of presenting only the meat, Pavlov always rang a bell at same time; through repetition, the dog would associate the two “stimuli” (meat and bell) and salivate as soon as the bell rings.

This idea is quite versatile when we move it into the realm of data science: instead of training puppies, we could build a machine that makes portfolios in the financial market and adjusts the combination of long/short assets depending on the “reward” (Financial return) of the previous portfolio and the evolution (“states”) of the market. Or a car that drives “by itself”, making decisions depending on the scenery it sees around, receiving negative rewards when it collides with the environment or with other vehicles, and with repeated steps, gradually “learns” to get round the obstacles.

Let’s go further: by going back to the example of dog training, suppose that you’ve successfully taught him to sit down, and now you want to do an obedience test - make the dog sit as you walk backwards, until you reach a five feet distance from it. If the dog sits down, you give it the cookie (as before); But if it does not get up until you’re five feet away from it, you give it a bigger reward (a piece of steak, for example). How could the dog earn the bigger reward? Note that now the dog has a “tough choice”: it can simply sit (since it has already learned this task) and always win the cookie, just as it can “explore” new possibilities - in the case, standing still with the owner away - to see if there is possibly a even greater reward. The owner will continue to provide positive and negative reinforcements as he walks backwards, praising the pet if it sits still and reproaching it if it leaves the position; But is the animal willing to give up the reward he already has “guaranteed”?

This situation illustrates a trade-off: the animal may choose to “test” new combinations of optimal actions in a sequence of previously unrealized “states” in pursuit of a larger but not immediate reward (the so-called “exploration”); Or simply to stick to the reward that is obtained through an already known action (the so-called exploitation). Note how this idea can easily extend to other contexts: In finance, for example, this reflects well the risk aversion degree of an economic agent - how willing he is to take more risks in search of larger returns, or is willing to take less risk and get a smaller, but safer return.

Making the machine being able to find the optimal middle ground between “exploration” and “exploitation” is one of the main challenges of reinforcement learning, and is quite relevant for more complicated applications, such as teaching a machine to play chess, for example: As is well known, a winning strategy often involves giving up immediate advantage, or even sacrifice pieces, aiming for long-term success - a good player should be able to take into account his moves’ consequences several rounds ahead, knowing that the opponent’s response will also be aimed at a future benefit, and so on.

Which one of those three approaches is the best?

The answer to this question depends on what you are analyzing. Each problem has its peculiarities, and a solving method that worked well for the problem A can be disastrous for another problem B. Therefore, when working with computing, data science, machine learning, or machines in general, keep in mind the following “law”:

THE MACHINE DOESN’T DO WHAT YOU WANT: IT DOES WHAT YOU COMMAND!

The machine is, above all, an instrument of convenience; The performance of artificial intelligence is entirely conditioned to the human intelligence of who trained it. Issues such as the bias-variance dilemma require careful attention from the researcher in order for the machine to actually provide the required results. Regularization and cross-validation techniques are also important mechanisms to “guide” the machine and guarantee a compromise between accuracy in the sample and generalization power. “Knowing how to command” is something that no machine can do for you. So knowing well the problem to be solved is always the first step, because this is the essential step for the researcher to have control over the machine, instead of the opposite…